Greetings! I’m Edward Hasbrouck, “The Practical Nomad”.

Who am I? The superficial answer is my current professional biography. Where do I come from? Here’s an article about the town from which my family name is derived.

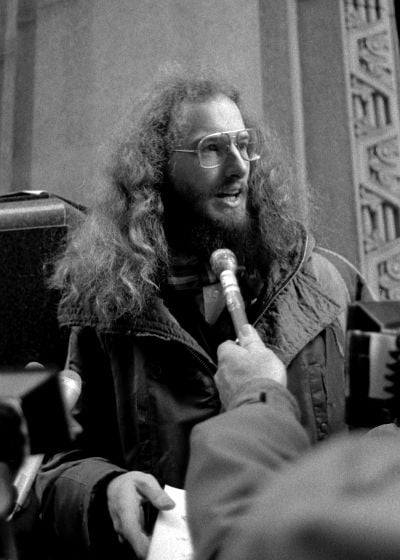

Few people are easily pigeon-holed or defined by descriptions like these, however, and I hope that I’m not one of them. My high school classmates voted me “Class Enigma” as well as “Most Intellectual Boy”, as I was captioned in this photo in my high school yearbook. (The “Most Intellectual Girl” in my class was Joann Stock, who went on to a distinguished career as a professor at Caltech.) My hometown newspaper once headlined a feature about me, Who is Ed Hasbrouck, and why is he bucking the system?

Part of my answer to some of these questions about why and how I think differently is that I have some degree of Asperger’s syndrome. I could describe this as a “self-diagnosis”, but to call it a “diagnosis” would be to suggest that it’s an ailment or a disability, rather than simply (or complicatedly) a difference. I’ve come to recognize Asperger’s as an asset, even when it sometimes causes problems for me. I’m not the only political activist to see my Asperger’s as related to my atheism, anarchism, and pacifism. But’s that’s certainly not the whole story.

Nor does my professional biography tell the whole story of who I am. I’ve done a variety of things, even a variety of noteworthy and publicly noted things; been involved with a variety of issues and organizations; and written and spoken about a variety of topics. There are links to this page from many other Web sites. It’s hard for me to predict what will have brought you here — travel, international airfares, freedom of movement, human rights, draft resistance, youth liberation, or Kashmir, for example.

What follows is a somewhat long, digressive, and self-analytical autobiography. It’s intended for people who already know me, or who have already read some of my other writings — on the Internet or in print — and are curious about how I define myself, or how I see my work and my persona fitting together. Don’t take it as representative of my other writing. You’ll get a better sense of my usual writing style, and what I have to say, from the rest of my Web site.

[Photo above in the Wellesley High School library by my classmate Paul Garmon from the 1977 Wellesleyan yearbook.]

So who is Edward Hasbrouck, anyway? It’s a surprisingly difficult question for me to answer, as the coherence of my interests and activities isn’t always easy for others to see — or for me to explain.

I grew up in Wellesley, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston on the Route 128 belt highway. At the time, Route 128 was known as the world’s foremost center of computer and other high-technology research and development. On my father’s side of the family, I’m the child, grandchild, and great-grandchild of engineers. My birth certificate actually says that I’m the child of a computer program (“Father’s Occupation: Computer Program”), which would be kind of cool if it were true. Back in 1960, I guess the City Clerk — even in Cambridge, MA, then as now a center of computer research and development — didn’t know what a “programmer” was.

My father started working as a computer programmer in the 1950s, and spent more than 20 years with Digital Equipment Corp., ending in their international division. He was proudest of his two years with a NASA contractor during the space race, during which we got a taste of life in Texas where he was working at the Johnson S[pace Center. Our junior high school in Wellesley had computers available to students by 1970. I’ve never been a hacker, but computers and technology have never held any fear for me either.

I consider myself primarily a political activist, first and foremost for youth liberation. I started down this path by fighting back against my violent and abusive father. Violent, I should note — not in my father’s defense but in indictment of the society whose values he expressed and tried to perpetuate — to a degree that was, at the time, both normative and generally approved of. But illegitimate nonetheless, as I always (fortunately) recognized, never succumbing to the pressure to internalize the lesson that I deserved my oppression.

I continued my resistance to the violence of illegitimate authority as an elected but nonvoting student representative to the local school board and as an activist for peace, disarmament, and students’ rights. My first book was a handbook for high school students on their legal rights which I co-authored in the summer of 1977, between high school and college, as an intern for the student service bureau of the Massachusetts Department of Education. (The last time I checked, an updated edition was still in print.)

I majored in political science at the University of Chicago (in the footsteps of earlier U. of C. students who would later be among my mentors, including Karl Meyer and Eric Weinberger) until I left college to pursue direct involvement in political activism.

[In front of the Federal courthouse in Boston before being sentenced for refusing to register for the draft,

14 January 1983. Photo © Ellen Shub. All rights reserved.]

In 1980, after a five-year hiatus, the U.S. government reinstated the requirement that all young men register for military conscription with the Selective Service System. In 1982, I was selected for criminal prosecution by the U.S. Department of “Justice” (specifically, by “U.S. Atty. William Weld”:/draft/draft/Marguerite-unpublished-22DEC1982.pdf and Asst. U.S. Atty. Robert Mueller) as one of the people they considered the “most vocal” of the several million nonregistrants for the draft. As one of 20 nonregistrants who were prosecuted before the government abandoned the enforcement of draft registration, I was convicted and “served” four and a half months in a Federal Prison Camp in 1983-1984. The high-profile trials of resistance organizers proved counterproductive for the government. Our trials served only to call attention to the government’s inability to prosecute more than a token number of nonregistrants, and reassured nonregistrants that they were not alone in their resistance and were in no danger of prosecution unless they called attention to themselves.

There’s more here about my prosecution for draft resistance, including links to many primary sources.

Why didn’t I register for the draft? There are many good and sufficient reasons to oppose, and to resist, military conscription. Not all of them relate specifically to war, and my resistance to the draft and draft registration was not primarily anti-war (although I was certainly afraid that Ronald Ray-gun would order a nuclear first strike that would kill us all, as I would later be afraid that Donald Trump would start World War III in a temper tantrum).

Conscription of young people to fight old people’s wars is one of the ultimate expressions of ageism, and for me, resistance to an ageist draft was first and foremost a component and continuation of the struggle for youth liberation. The religious and authoritarian justifications for conscription and war are remarkably similar to the religious and authoritarian rationales for violence against children and for slavery. And the same ageism underlies state-sanctioned and state-enforced parental ownership and authority over children, state-enforced compulsory schooling, and military conscription (or other compulsory national service).

As I explained in the letter to the government that led to my selection for prosecution and in the letter to the judge that led to my imprisonment, my resistance to the draft was motivated primarily by pragmatism: I thought resistance to draft registration could prevent a draft (as, in fact, it did) and thereby at least marginally inhibit warmongering (which I think it did, although only to a limited degree). Ideologically, my resistance was primarily anti-ageist, secondarily anti-authoritarian, and only to a tertiary degree anti-militarist or anti-war.

(More than a decade earlier, in 1969, Tom Hayden testified to a Federal commission of inquiry about that same trio of motivations for draft resistance. While the anti-draft movement of that era had emerged out of the anti-war movement, anti-draft activists had come to see their opposition to the draft as also motivated by their opposition to the undemocratic, authoritarian character of the draft itself, and by its ageism.)

I see atheism, anarchism, and pacifism as three different ways of describing the same worldview, not as independent axioms. In my mind, atheism, anarchism, and pacifism are logically equivalent. Each can be derived from the others, and all three are expressions of a common epistemological perspective. All three played a role in my decision not to register for the draft. That perspective is inherently subjective and relativist, which leads to my ambivalence about both voting and nationalism. I sometimes vote, but it’s a situational choice: I did vote from prison once, for example.) Another way to explain my nonregistration for the draft is that the burden of proof was on the government to justify its demands, not on me to justify my inaction. The government’s failure to meet its burden of proof was sufficient reason not to register for the draft.

I was and am a draft resister, not a conscientious objector. How to respond to the draft, like whether or not (or in which elections) to vote, whether to resist openly or covertly, or how to relate to the contradictions of nationalism, are for me political choices — choices to be made with care — not moral duties. I’ve tried to learn, in making those choices, from mentors who have included Eric Weinberger, Dave Dellinger, andDavid Harris, among many others.

Registration with the Selective Service System for a possible draft remains the law for young men in the USA, but no one has been prosecuted for resistance to registration or the draft since 1986, and the government abandoned all further attempts to investigate or prosecute nonregistrants in 1988 after the first 20 test cases had played out. Nonregistration — mass direct action against draft registration — has prevented reinstatement of the draft. I’m proud to have played the role I did in that campaign, and of the work I continue to do to support the next generation of draft resisters and their efforts to liberate themselves and to protect us all from the larger, longer, and more unpopular wars that the perceived availability of a draft enables. In 2021, I received a Social Courage Award

from the Peace and Justice Studies Association “for exemplifying courage and honor in speaking truth to power” in my ongoing anti-draft activism.I remained active in the peace movement and the National Resistance Committee, moving to San Francisco in 1985 to join the editorial and production collective of Resistance News, the national newspaper of the draft resistance movement. I remained involved in the anti-draft movement through its revival during the Gulf War, when the U.S. government came very close to reinstating a doctor draft of health care workers. I continue to make available new, updated, and historical resources on draft registration and draft resistance.

For the next several years, I earned my living mainly as a freelance graphic artist and publications coordinator for everything from a bicycling magazine to a distributor of laboratory apparatus. Meanwhile, I led preparation sessions for nonviolent direct actions and civil disobedience and became increasingly involved as a volunteer legal worker, legal educator, and participant in legal defense and organizing collectives for arrested peace and disarmament activists from various campaigns.

Travel and politics first intersected for me on a trip in 1989 to Kashmir. It’s an important part of my personal journey, which I’ve written about in a separate section of my Web site and won’t repeat here.

While my partner Ruth, my mother, and I were in India and Pakistan, national flags were burned by dissidents and critics of governments and their policies in both countries, as they had been before and have been since in many other countries. I paid particular attention to these incidents, and the varied public reactions to them, because the USA Congress had that year begun to consider the possibility of amending the US Constitution (and repealing part of the First Amendment) to outlaw the use of USA flags to express disagreement with or hostility to the USA government.

My defense of the right to burn the USA flag to express whatever ideas one wants (and not just to burn flags to express reverence for the government through ritual disposal of soiled flags) was a natural outgrowth of my work on other political trials. I volunteered as a legal worker, organizer, and lobbyist for the defense committees for those prosecuted for flag “desecration” in the 1989 and 1990 Supreme Court flagburning cases. It was an intense, at times surreal, campaign. I was one of few people on speaking terms with both flagburners and Congressional aides. While the issue has largely faded from public view, I’ve tried to help maintain awareness of the threat it poses. Some of you may have seen me on C-SPAN and CNN and in other television appearances representing the Emergency Committee to Stop the Flag Amendment and Laws, and in a nationally televised debate on the Flag Consecration Amendment first broadcast on July 4th, 1997 on the Debates! Debates! show.

[On the steps of the Supreme Court following

oral argument in U.S. v. Eichman, 14 May 1990.

Behind me in close-up, left to right: Bill Kunstler,

Joey Johnson

(with keffiyeh), David Cole (mostly hidden behind me).

From C-SPAN video.]

I’m proud to have taken a stand on the issue of the flag, free speech, and fascism, but I’m disturbed that the outcome remains in doubt: the “Flag Consecration Amendment” to the US Constitution has been introduced in Congress repeatedly, and each time has come closer to passage. The Flag Amendment was approved by majorities of both the Senate and the House of Representative in 1989, 1990, and 1995, each time by a larger majority. In 1995, it was approved by 2/3 of the House and fell only 3 votes short of 2/3 in the Senate. In 1997. 1998, and 1999 it was approved again by 2/3 of the House. And in 2016, Joey Johnson was again arrested for burning a flag outside the Republican National Convention, this time during the nomination of the fascist Donald Trump.

[On the lawn of the U.S. Capitol, gagged with a U.S. flag, 21 June 1990,

as Congress was voting on whether to amend the U.S. Constitution or pass a new law to outlaw the “desecration” of the U.S. flag.]

I began working as a travel agent quite accidentally. I was out of (paid) work after one of several periods in my life of unpaid full-time political activism, and I happened to be offered a job with an around-the-world specialty agency willing to give sufficiently well-traveled and quick-learning people a chance at on-the-job training. (There are some trade schools for travel agents, but even most travel school graduates start out as unpaid interns or apprentices.) I stayed in the travel “industry” for 15 years, to the surprise of many of my political friends—because of, not in spite of, my values and goals.

My work as a travel agent, travel seminar leader, and travel writer has given me, for the first time, the chance to integrate my paid employment with my global concerns and my work for social change. Much of my activism is rooted in, among other things, transnationalism. It goes back at least as far as my year as a high school student researching and debating the question, “Resolved: that the development and allocation of scarce world resources should be controlled by an international organization.” I’ve long tried to think in global, not national, terms, and to act for the global good, even before I came to draw inspiration from globalist theoretician/activists like Nehru, Gandhi, and Ambedkhar, or to define myself as an anarchist and a pacifist as well as an atheist. Wherever I go, I try learn about local issues, not just see tourist sights, whether with my ongoing interests in Kashmir and South and Central Asia or with places I’ve visited more recently like Argentina, or South Africa, Syria, and Yemen.

[Sana’a, Yemen, 2008. Before we start bombing people, we ought to learn something about who they are.

It’s easy to demonize people we’ve never met who live in places we’ve never been and can’t really visualize.]

Working as a travel consultant paid my rent for more than 15 years, but I didn’t stay in it for the money. Frankly, most jobs that would use as many of my skills, or require as much or as diverse knowledge, skill, and expertise, would pay much better. And if my goal were to travel, I’d be better off working another job that would give me more time off and pay enough to more than offset the value of the limited travel benefits of the job. (There’s a longer discussion of the work of travel agents, and the lack of respect they get, in The Practical Nomad: How to Travel Around the World.) I stayed in this line of work because of the opportunities it has given me to facilitate learning and to empower people to experience the world for themselves.

I began writing about privacy and the potential (commercial) abuse of travel records as an important consumer issue for travellers. That’s the way i talked about it in The Practical Nomad Guide to the Online Travel Marketplace, which was published in early 2001. After 11 September 2001, the privacy of travel records became an issue of government surveillance and attempted control of movement (as well as continuing to be one of consumer privacy). As perhaps the only leading “privacy advocate” or consumer advocate for travellers with technical expertise in airline and reservation data and how it is used, I’ve been able to have a unique role in debates on this issue. Since 2007, my work has included consulting with the Identity Project on travel-related civil-liberties and human rights issues. For what it’s worth, this is the first time I’ve ever been paid for any of my explicitly “political” work, although it’s work I believe in, would be doing, and already was doing — with or without pay. John Gilmore, the founder and principal underwriter of the Identity Project, told an interviewer a few years ago that, “I would not encourage anyone to desert the people who depend on them — such as their children — in order to be an activist. Having said that, in a free market for labor, it is often possible to find an employer who is supportive of your activism. The best kinds of jobs are the ones that you would’ve been doing whether they paid you or not.” That certainly described my work with the Identity Project. Thank you, John!

Learning isn’t necessarily your goal in travel, but experience almost always is. And learning is, I believe, a natural consequence of experience.

[These World Heritage Sites in Syria that I visited in 2008 have all been damaged or destroyed in subsequent fighting. Left to right:

Al-Madina souk (Aleppo);

Umayyad Mosque (Aleppo);

Roman city of Palmyra. More important than seeing these sites, however,

was getting to talk to people in Syria and Yemen — among the high points

of my most recent trip around the world — before the US government and military got involved in the wars in those countries.

How much do we really know about who is being shot at with bullets our taxes have bought, or why?]

It takes real effort to close one’s mind enough not to learn from experience. In my opinion, one of the greatest evils is the deliberate avoidance of learning, the willful desire not to know (lest knowledge bring with it an awareness of reasons to change one’s actions). But most people want to learn. For me, it’s a privilege (and a responsibility) to get paid to help people — travellers — who are choosing to devote a portion of their lives to experiencing, and thus learning about, the world and their place in it.

A corollary of my atheism is my belief that experience and direct perception are the ultimate sources of all truth and real knowledge. More bad things result from ignorance than from malice. Lack of knowledge makes it easier for a few malicious people to get away with things that others wouldn’t tolerate were they aware of them. All sorts of exploitation and repression can be rationalized to people who have no direct information with which to rebut the lies of omission and commission. Secrecy and ignorance are the first friends of oppressors everywhere.

One reason, for example, that it’s so easy for the USA to get away with big lies about Cuba, for India to get away with big lies about Kashmir, or for China to get away with big lies about East Turkestan (of which there is so little awareness that China scarcely even needs to lie) is that almost anything can be made to sound plausible to people who haven’t been there and have no direct knowledge of a place or a people.

Does this mean I have a hidden agenda for your travels? No. My agenda is open: to get you to go, to see, and to experience the world for yourself; to draw your own conclusions; and to act on them as you see fit.

Do I insist that you see things my way? Certainly not. Everyone has their own, to them equally true-seeming, sense of truth. Pacifism and anarchism (which to me are different terms for the same concept) imply believing in the illegitimacy of any attempt to force my beliefs on others, and recognizing that the ultimate human right is each person’s right to be respected in the sincerity and equal validity of their own sense of truth.

Gandhi defined “Satyagraha” (often translated “nonviolence”) as “truth force”. By this he meant, I think, to express the equivalence of renouncing violence and relying on people’s ability and desire to make decisions for themselves. To renounce coercion, as I do, is to trust that, if my beliefs are valid, others who seek the truth through experience and observation will reach the same conclusions, or persuade me that I am wrong. All I can ask of you or anyone is that you keep your eyes, ears, senses, and mind open to perception, experience, learning, knowledge, and change — as I try to do myself.

Peace,

Edward Hasbrouck

About | Bicycle Travel | Blog | Books | Contact | Disclosures | Events | FAQs & Explainers | Home | Mastodon | Newsletter | Privacy | Resisters.Info | Sitemap & Search | The Amazing Race | The Identity Project | Travel Privacy & Human Rights

This page published or republished here 5 April 1999; most recently modified 12 January 2024. Copyright © 1991-2024 Edward Hasbrouck, except as noted. ORCID 0000-0001-9698-7556. Mirroring, syndication, and/or archiving of this Web site for purposes of redistribution, or use of information from this site to send unsolicited bulk e-mail or any SMS messages, is prohibited.