The United States vs. Edward Hasbrouck

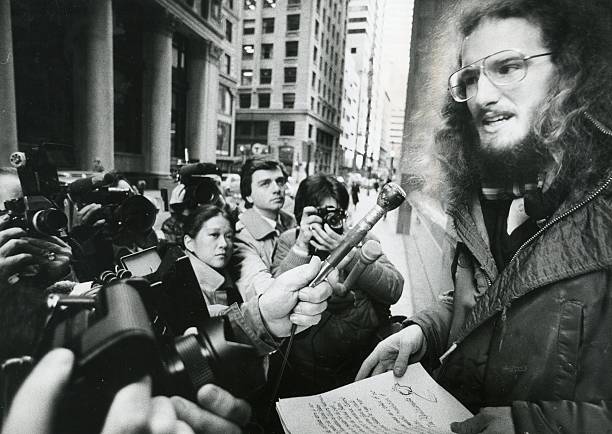

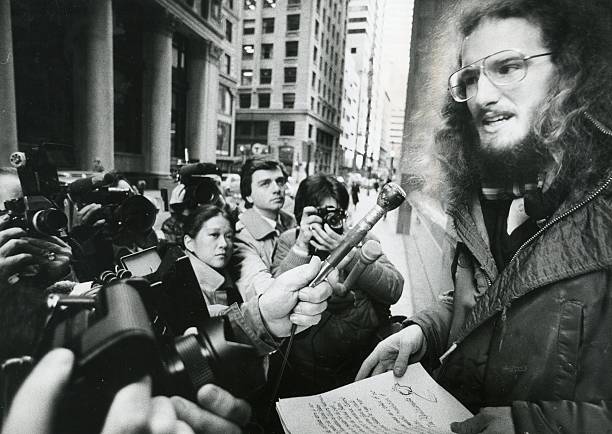

[Outside the Federal courthouse in Boston before my sentencing for refusal to register for the draft, 14 January 1983. I’m holding a copy of the statement from the anonymous Abolitionists who had locked the courthouse doors the night before. Photo by Tom Landers, Boston Globe, via Getty Images. (More unpublished photos from the Boston Globe archives at Northeastern University.)]

This is a general Web site about the current status of military conscription in the USA and the histoiry of draft, draft registration, and draft resistance in the USA since 1980. But for those who are interested, this page is an introduction to my personal draft resistance story.

I was one of 20 people prosecuted in the 1980s in the USA for refusing to register with the Selective Service System.

Nonregistrants weren’t the only draft resisters to be prosecuted. Many more allies who weren’t themselves subject to the requirement to register for the draft, notably including the Boston 18, were prosecuted for sit-ins, blockades, and other draft resistance actions at Post Offices (which were used as draft registration sites), courthouses where nonregistransts were on trial, and Selective Service System offices.

The case of the U.S. against Edward Hasbrouck is also the case of the U.S. against each of us, and against others who are not here today. His indictment is also an indictment of our work, of our beliefs, and of our feelings against registration, the draft, militarism, and war.

[from a statement read to the court during my arraignment for knowing and willful refusal to register with the Selective Service System, 14 October 1982]

In 1980, after a five-year hiatus, the U.S. government reinstated the requirement that all young men register for military conscription with the Selective Service System. In 1982, I was selected for criminal prosecution by the U.S. Department of “Justice” (specifically, by U.S. Atty. William Weld and Asst. U.S. Atty. Robert Mueller) as one of the people they considered the “most vocal” of the several million nonregistrants for the draft. As one of 20 nonregistrants who were prosecuted before the government abandoned the enforcement of draft registration, I was convicted and “served” four and a half months in a Federal Prison Camp in 1983-1984. The high-profile trials of resistance organizers proved counterproductive for the government. Our trials served only to call attention to the government’s inability to prosecute more than a token number of nonregistrants, and reassured nonregistrants that they were not alone in their resistance and were in no danger of prosecution unless they called attention to themselves.

Edward Hasbrouck has taken an honorable and courageous step towards preventing g1oba1 catastrophe. He should have the support of people who are committed to peace and justice.

[Noam Chomsky, December 1982]

There were actually three Federal criminal cases brought against me as “The United States of America versus Edward Hasbrouck”:

- I spent 35 days in the Federal Correctional Institution in Danbury, CT, in July-August 1982 for hugging my fellow nonregistrant Russ Ford in an act of solidarity in resistance to draft registration. This was widely misreported and misunderstood, although there was a demonstration outside the entrance to the prison complex at Danbury in solidarity with Russ and me. I thought my action was a fairly straightforward expression of, “An arrest of one will be considered an arrest of all,” as I had said in earlier pledges of solidarity. I was initially indicted for “assaulting” U.S. Marshals “by embracing one Russell Ford while he was in the custody of the United States Marshal and his Deputies”, but eventually this indictment was replaced by an information (complaint) that I violated Federal building regulations by “failing to disengage from Ford after being directed to do so by said United States Marshal and his Deputies”.

- I was convicted and incarcerated for 4 1/2 months in a local jail near Boston, in Danbury again, and for most of my sentence in the Federal Prison Camp in Lewisburg, PA, in 1983-1984 for having knowingly and willfully refused to submit to registration with the Selective Service System. I was originally sentenced to probation with a special condition that I do “community service” acceptable to the Court, but my probation was revoked and I was resentenced to prison after the sentencing judge disapproved of the political statement made by my community service.

- Shortly after my initial suspended sentence for refusing to register, I was at the courthouse for a hearing in another case when, finding the courtroom unlocked and unguarded, someone else put up Resist the Draft. Refuse to register. You won’t be alone stickers in the courtroom, an incident reminiscent of how, when U.S. Marshals came to the Struggle Mountain resistance commune in the Santa Cruz Mountains above Palo Alto to arrest Davis Harris in 1969, someone put a Resist the Draft sticker on the back bumper of the Marshals’ car. Some of the guards at the courthouse in Boston — angry and embarrassed by the stickers and displeased that I had been given only a suspended sentence for refusing to register for the draft — assaulted me and several activists who were with me, and tried to frame me and Liz Davidson for felony assault on Federal officers. We were acquitted by a Federal jury, a rare event then and even rarer still today, especially in a case which rested entirely on our word against that of Federal police. (This was before there were video or audio recordings of such police encounters.) We told the jury that the police were lying and trying to frame us, and why they had a personal animus against us. The jury believed us. This police frame-up for “assault by cop”, and our successful defense against it, warrants a more detailed account which I have yet to write.

I wrote about many of these events in a long open letter from Lewisburg Prison Camp in January 1984 that was published as the lead article in Resistance News #14 (March 1984). But the summary below may provide some context that readers of Resistance News might not have needed.

The first question I am asked is often, “Why didn’t you register for the draft?” At a more nuanced level, why I didn’t register when the government wanted me to do so, why I spoke out publicly about it, and why I informed the government of my refusal to comply with its demands, are distinct questions.

There are many good and sufficient reasons to oppose, and to resist, military conscription. Not all of them relate specifically to war, and my resistance to the draft and draft registration was not primarily anti-war (although I was certainly afraid that Ronald Ray-gun would order a nuclear first strike that would kill us all, as I would later be afraid that Donald Trump would start World War III in a temper tantrum).

There are many good and sufficient reasons not to register; among them are love of country, love of life, love of freedom, love of peace and simple (?) love. Of my own reasons, suffice it to say that a democratic decision that a nation should use force can only be made by people who freely choose to wield that force…. Enough apology. I’ve grown tired… of explaining again and again why I didn’t register. I’m proud… that I didn’t register, and I don’t owe anyone an explanation. It is I and my friends who deserve an explanation: Some strangers, none of whom did I elect and only a handful of whom have I ever had the chance to vote against, have broadcast that [they] want me to file with their agents a statement of where they can find me should they ever wish to summon me to surrender my civil rights, submit myself to a course of indoctrination… and go to some strange place of their choosing to kill, promptly at their command, other strangers of whose language and values I would probably be ignorant and on whose land I would probably be trespassing…. Why should we register?

[Open letter from Edward Hasbrouck to The Peacemaker, 7 April 1981]

As I explained in the letter to the government that led to my selection for prosecution and in the letter to the judge that led to my imprisonment, my resistance to the draft was motivated primarily by pragmatism: I thought resistance to draft registration could prevent a draft (as, in fact, it did) and thereby at least marginally inhibit warmongering (which I think it did, although only to a limited degree). Ideologically, my resistance was primarily anti-ageist, secondarily anti-authoritarian, and only to a tertiary degree anti-militarist or anti-war. (See more about my personal philosophy and more here and here about how how my work against the draft relates to my work on other political and social issues.)

Conscription of young people to fight old people’s wars is one of the ultimate expressions of ageism, and for me, resistance to an ageist draft was first and foremost a component and continuation of the struggle for youth liberation. The religious and authoritarian justifications for conscription and war are remarkably similar to the religious and authoritarian rationales for violence against children and for slavery. And the same ageism underlies state-sanctioned and state-enforced parental ownership and authority over children, state-enforced compulsory schooling, and military conscription (or other compulsory national service).

(More than a decade earlier, in 1969, Tom Hayden testified to a Federal commission of inquiry about that same trio of motivations for draft resistance. While the anti-draft movement of that era had emerged out of the anti-war movement, anti-draft activists had come to see their opposition to the draft as also motivated by their opposition to the undemocratic, authoritarian character of the draft itself, and by its ageism.)

A thing I was thinking about initially [when I decided not to register for the draft] was the fascism of it. Fascism is a word a lot of people don’t like. But I think it’s important to say. Draft registration is part of the fascist menace in America. It’s an effort at very severe control of people by the government. And this is something that’s true quite apart from the precise purposes that people are being controlled for. It’s dangerous and it’s anti-democratic and it’s being used as an excuse for a lot of other kinds of efforts toward greater social control.

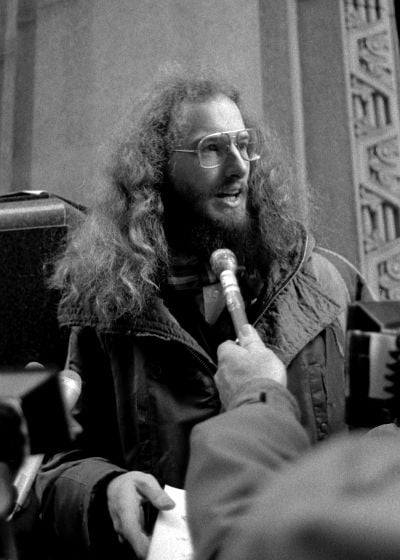

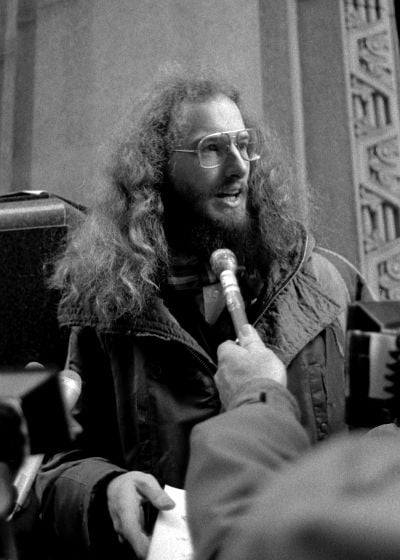

[Edward Hasbrouck, interviewed by Stardust Doherty on 13 January 1983, the day before my sentencing for refusal to register for the draft, published in Resistance News #12, March 1983.]

When I was first required to register in July of 1980, I spoke out publicly about my refusal to register. By doing so, I hoped to empower and encourage other young people to come out as nonregistrants, and to make nonregistration visible. If all nonregistants remained closeted, and none gave the phenomenon of mass noncompliance a public face, it would be easier for the government to pretend that all draft-age men had registered, and to act — and plan for unlimited wars — as though the draft was a possibility.

My name is Edward Hasbrouck. I am 20 years old, a natural-born United States citizen, and, for what I do today and will do in the weeks to come, a federal felon. I urge you to join me in felony.

Consider, if you will, the absurdity of my position. I am here to explain — to justify — my belief that thou shalt not kill. I am here to tell you why I do not want to be a murderer, to be a slave, to join a cult, or to be brainwashed. I am not, and will not be, a tool to be used against another person by still a third. To me, who was born with the Sixties and who grew up with the Vietnam War, it is evident that force is not and cannot be an instrument of progress. Faced with those who would use force — or, more likely, have others use force — I feel as one who, confronted with the ravings of a madman, must explain to him why those ravings make no sense.

[Statement at press conference in Chicago, 17 July 1980, just before the resumption of draft registration.]

By refusing to register, I opted myself out myself of any risk of being drafted. By speaking out about my nonregistration, I was trying to prevent anyone from being drafted and to impede war planning and war preparations:

Some nonregistrants, motivated by Gandhian or other philosophies of civil disobedience, notified the government of their refusal to register. I didn’t initially do so, feeling no obligation to assist the government (whose authority I did not recognize) in locking me up. But in October 1981, when the government began threatening to make examples out of selected nonregistrants, and moved in part by the example of solidarity actions among an earlier generation of draft resisters during the U.S. war in Indochina, I wrote to the government to inform them of my solidarity with those being threatened with prosecution for the same crime that I too had committed:

Only a token fraction of those who don’t register can or will ever be prosecuted. You are now preparing for just such token prosecutions of… selected non-registrants. This letter is an expression of my solidarity with all those who may be prosecuted. They are not alone: I shall place myself with them, and I pledge whatever nonviolent action that solidarity may require. In prosecuting any, you prosecute all, and I shall act accordingly. I expect to be prosecuted for writing this letter.

[Edward Hasbrouck, open letter to the U.S. government, 3 October 1981]

When Russ Ford became the first New Englander since the U.S. war in Indochina to be indicted for nonregistration, I attended his arraignment in Hartford, CT. Russ declined to promise to appear for trial if released on his own recognizance. As he was being taken into custody, I hugged him, forcing the Federal Marshals to take us both or let us both go. Unsurprisingly, they took us both, and I was charged with assaulting Federal officers by embracing one Russell F. Ford. Despite being perfectly healthy, we were locked up together in the medical isolation room of the hospital at the Federal Correctional [sic] Institution in Danbury, CT, apparently out of fear on the part of the Bureau of Prison that our political ideas might prove contagious and infect the general population.

[Edward Hasbrouck at F.C.I. Danbury in August 1982. I wasn’t allowed ordinary visitors, but Jim Motavalli from the New Haven Advocate got in to interview me, along with a photographer, and later sent me this outtake from that photo shoot.]

A little over a month later, Russ agreed to accept release on his own recognizance, and I agreed to allow an Alford plea of guilty to be entered for me to a reduced charge of violating Federal building regulations “by embracing one Russell Ford while Ford was in the custody of the United States Marshal and his Deputies and by failing to disengage from Ford after being directed to do so.” I was sentenced to 30 days time already served; Russ was eventually sentenced to time served for his refusal to register. Russell and I have remained friends for life.

In a classic case of the left hand not knowing what the right hand was doing, while I was in Federal custody in Connecticut two FBI agents assigned to investigate my refusal to register came looking for me at the group house in Boston where I had been living. After my teenage housemate Jeffrey Weinberger told them, “We don’t talk to the FBI,” and shut the door in their faces, they copied down the license plate numbers of of all the cars parked on the block (none of which belonged to anyone in my household) and then went away. With unconscious irony, they reported to the U.S. Attorney’s office that “Efforts to interview Hasbrouck at his residence were unavailing.” I was indicted for my own nonregistration shortly after my release from Danbury for hugging Russ.

[My indictment for refusal to register for the draft, signed by the foreman of the Grand Jury and by Assistant U.S. Attorney Robert S. Mueller, III.]

I was prosecuted for refusal to register by former Marine Lieutenant and platoon leader in Vietnam Robert Mueller,

then a junior Assistant U.S. Attorney, later Director of the F.B.I., and more recently Special Counsel in charge of the investigation of Russian government interference in the 2016 Presidential election.

Like John Kerry, Mueller graduated from an Ivy League college, then volunteered for the military out of a sense of noblesse oblige.

But while Kerry came back from Vietnam having learned that the war was wrong, and became active in the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (and went on to a career in electoral politics including as Senator from Massachusetts), Mueller came back from Vietnam still believing in the war and the draft — as evidenced by his eagerness to prosecute draft resisters even in an obviously unsympathetic district like Massachusetts. Muller’s failure to learn from his experience in Vietnam suggests that his commitment to “principle” is more a commitment to dutifully following orders than a commitment to following one’s conscience. Mueller was a good soldier. He follows orders. He was and is a good prosecutor who saw, and probably still sees, his role as prosecutor

as waging war — war on communism, war on crime, war on terror, etc. — by other means.

Mueller’s boss, William F. Weld — then U.S. Attorney, later Governor of Massachusetts, and later still 2016 “Libertarian” candidate for Vice-President of the USA — also attended my trial to observe his protegé Mueller’s performance in court.

My case was Mueller’s first high-profile trial, and my head was a significant early stepping stone in his political climb.

Mueller was first brought to public notice in a front-page column by World War II veteran David Farrell in the Boston Globe on 20 December 1982, just after my trial, under the headline, Prosecutor’s the Hero:

The courtroom contrast was striking between Hasbrouck, who said he is “prepared to go to jail” to support his convictions, and [Asst. U.S.] Atty. Mueller, who spoke in measured tones about the need to uphold the law…. Mueller is not well known in this area…. His resume reveals an extensive and impressive background in criminal law which is surpassed by his outstanding record during 33 months in the US Marine Corps…. The judge, who has a reputation for being lenient, can let Hasbrouck off with an alternate sentence in a school for the retarded or even a suspended term. US Atty. Weld, who happened to sit next to Hasbrouck’s mother throughout the trial, is expected to ask Judge Nelson for a jail term when he makes his recommendation next month.

This was an opinion column, but the Globe’s news coverage of my case was no more sympathetic or objective. The Globe’s full-time staff reporter at the Federal courthouse, William Doherty, was an old-school police-beat hack who identified with the police and hung out with the courtroom marshals in his spare time — not like the more recent norm of journalism-school and in some case law-school trained legal reporters. The Globe’s William F. Doherty was no relation to Will Doherty (today Stardust Doherty), my comrade in Mass Open Resistance and an occasional contributor to the Gay Community News. But the similarity in names confused some readers, since my friend Will was a journalism major at MIT and might plausibly have been interning for the Globe. When I was indicted, the Globe’s reporter didn’t call my parent’s home at the phone number listed in the name of Hasbrouck at the address in Wellesley given for me in the indictment. (They later changed to an unlisted number because of hat calls about their draft-dodger son, but not until later.) Instead, the Globe’s reporter started calling random Hasbroucks in other towns in Boston-area phone books. Another friend of mind, curious about the story in the Globe, later went through the same routine of calling Hasbroucks listed in area phone books and found the person who had talked to the Globe. They described the conversation as follows:

“This is William Doherty. I’m a reporter with the Globe, trying to track down an Edward Hasbrouck. Do you know him?”

“No.”

“Are you related?”

“Probably. We’re all distant cousins.” (I might have said the same thing, if I had been asked, but the key word here is “distant”. Almost all the Hasbroucks in North America are descendants of two Hasbrouck brothers who came to what is now the USA more than 300 years ago, and we’re all at least 10th cousins. I never met any other Massachusetts Hasbroucks, but Doherty may have inferred, without inquiring further, that this was a close-knit extended family in which everyone knew everyone else.)

“Do you you know where he might be? He was just indicted for draft resistance.”

“I don’t know. Maybe he went to Canada?”

William Doherty’s story in the Globe the next day — the first news that most of my neighbors or potential jurors heard of my indictment — included the sentence, “The Wellesley man indicted, Edward J. Hasbrouck of Elmwood avenue [sic; actually Elmwood Road], could not be reached for comment. A woman identifying herself as a cousin of Hasbrouck’s said he left Tuesday for Canada.” Doherty’s courtroom coverage went downhill from there. The best report on my trial, two months later, wasn’t in any of the local Boston-area papers but a front-page feature by Berkeley Hudson in the Providence Journal.

The instructions from the Justice Department to U.S. Attorneys were to seek indictments of nonregistrants only in the most “sympathetic” Federal districts, so as not to stir up anti-nuclear, anti-war, and student activists. Most U.S. Attorneys in big cities and liberal districts chose not to seek indictments in the cases that were referred to them, and the District of Massachusetts was the epitome of an “unsympathetic” district for prosecution of draft resisters,

If Mueller had been “just following orders” he would have declined to prosecute, as did more than 90% of the other Federal prosecutors to whom similar cases were referred. I’ve never found out how Mueller and Weld got permission to go after me in Boston, and I have no reason to think that either of them started out with any personal animus against me, rather than a general animus against draft resisters. But I infer that one or both of them — most likely Mueller — must have had sufficiently strong feelings about draft resisters to allow their political opinions to influence how they exercised their prosecutorial discretion.

[Poster by Liz Davidson for my trial for refusal to register for the draft, Boston, MA, 15 December 1982. More draft resistance graphics including other posters by Liz Davidson.]

My arraignment (photo), trial, and sentencing (see links below to transcripts and additional articles) in Boston were attended by draft resistance activists and supporters from throughout New England, New York state, and further afield, including campus and community activists, radicals and liberals, women and men, and several generations of resisters. That’s John Bach, who had been imprisoned for almost three years

for resisting the draft during the U.S. war in Vietnam, next to me in the courthouse elevator on the way to my sentencing. Also at my sentencing were Elmer Maas and Dean Hammer of the Plowshares Eight, and several other participants in “Swords into Plowshares” disarmament actions. Dave Dellinger, who was imprisoned for refusing to register for the draft during World War II and later had been one of the Chicago 8, came to my trial from Vermont and was one of the speakers at a teach-in at MIT the evening before my trial (if anyone has recordings, photos, or other records of who s[poke and what was said at that teach-in, please get in touch), as he had been one of the speakers at a teach-in at the University of Chicago the day I was first arrested, at an anti-war and anti-draft demonstration against Robert MacNamara in 1979.

[In front of the Federal courthouse in Boston before being sentenced for refusing to register for the draft,

14 January 1983. Photo © Ellen Shub. All rights reserved.]

So many supporters showed up for my trial that it was moved to the largest courtroom in Boston’s Federal courthouse in Post Office Square — the same room, I believe, in which Dr. Benjamin Spock, Rev. William Sloane Coffin, Michael Ferber, Marcus Raskin, and Mitchell Goodman had famously been tried in 1968 for conspiring to advocate draft resistance.

[Picket line outside the Federal courthouse in Boston before my sentencing for refusal to register for the draft, 14 January 1983. Clark Gilman at left with leaflets; James Groleau in center with “Support Ed Hasbrouck” sign. Photo by Tom Landers from the Boston Globe archives at Northeastern University.]

Three people — the “Chain Gang” of Eric Weinberger, Sean Herlihy, and Liz Davidson — were arrested for chaining themselves in the courthouse doors to prevent the trial from proceeding. Other persons unknown, calling themselves The Abolitionists in a statement they left behind, locked the courthouse doors with U-locks and plugged the keyholes with glue the night before I was to be sentenced:

[Locking the courthouse doors is our attempt to prevent the “United States of America” from sentencing Edward Hasbrouck for refusing to register for the draft. We can no more allow the “United States,” through this court, to sentence Edward Hasbrouck in our name than he could allow the “United States” to wage war in his name. We have left you roses as a token of our hope for the peaceful resolution of human conflicts. — The Abolitionists]

Hundreds of letters were sent to Judge David S. Nelson urging him to reject the prosecution’s request that he sentence me to prison. Judge Nelson initially ordered me to do 2,000 hours of community service.

[Poster by James Groleau for my sentencing for refusal to register for the draft, Boston, MA, 14 January 1983. More draft resistance graphics including other posters by James Groleau.]

By the time of my sentencing in early 1983, the Federal courthouse and Post Office (draft registration was being conducted primarily at Post Offices) in downtown Boston had become a focus of anti-draft pickets, sit-ins, and lockdowns, and the guards at the courthouse had developed a particular animus against draft resisters in general and me in particular. Dissatisfied with what they saw as too lenient a sentence from Judge Nelson for my refusal to register for the draft, they took matters (and took me and a friend) into their own hands the next time I was in the building, and tried to frame me and my comrade Liz Davidson on trumped-up felony charges of assault on Federal officers, which would have led to much longer prison sentences than refusing to register for the draft. The frame-up failed, and we were eventually acquitted by a Federal criminal jury (a rare outcome in such a case) mainly because the Federal Marshals and Federal Protective [sic] Officers (the predecessors of today’s Homeland Security Police) did such an inept job of perjuring themselves.

Almost a year later, after Judge Nelson objected to the political message expressed by my peace work, he imposed the six-month prison sentence that he had originally suspended, despite the quite brave testimony at my probation violation hearing by my probation officer, Esther W. Salmon,

that she believed that my peace work satisfied the terms of the judge’s order.

While in the Federal Prison Camp in Lewisburg, PA, I was denounced as yuppie in the pages of the New York Times by Rep. Gerald Solomon (sponsor of the laws denying Federal student aid, which I had never received anyway, to nonregistrants), for having taken the risk of speaking out about my resistance to the draft. (There’s more here about my experience in Lewisburg and more here about my personal reasons for refusing to register for the draft.

I never intended this to be a Web site about my personal history. I created this Resisters.info site as a general resource about the draft, draft registration, and draft resistance since 1980. But I keep getting questions about my own story, and it may be helpful as a case study. I’ve gradually been posting additional historical material, to the extent that I have permission to do so. I’ve sent copies of these and other related documents, and have willed the remainder of my political papers, to the Swarthmore College Peace Collection.

Public statements of refusal to register and of solidarity with other draft resisters:

- “I urge you to join me in felony.”

(Statement by Edward Hasbrouck at press conference in Chicago, 17 July 1980, just before the resumption of draft registration.)

- Community of Resistance

(Statement of solidarity initiated by Joe Maizlish and signed by Edward Hasbrouck and others, with list of signatories as of November 1980)

- Open letter to the Selective Service System

(by Edward Hasbrouck, 3 October 1981; published in Fifth Estate and elsewhere; introduced and read into the record in full as evidence against me at my trial)

- Registry for NonRegistrants

(Open letter from Edward Hasbrouck, 7 April 1981, endorsing statement initiated by The Peacemaker)

- “An arrest of one will be considered an arrest of all.”

(Statement by the National Resistance Committee, 19 November 1981, re: plans to respond to the indictment of a nonregistrant)

- Opponents of draft registration are geared to protest

(by Barbara Rosewicz, UPI, 19 November 1981. “‘We need to do whatever nonviolent acts we can do to make it impossible for the government to single out some of us,’ said Edward Hasbrouck, an organizer from Boston…. If prosecution is initiated against any of the men, Hasbrouck predicted others who have not registered will turn themselves in, ‘demanding that the government prosecute all of us or none of us.’”)

- The ACLU and anti-draft groups promised ‘every legal effort’ and ‘a season of nationwide protest’ against the prosecution of youths who fail to register for potential conscription.

(by Daniel F. Gilmore, UPI, 1 June 1982.)

Court, probation, and FBI records, evidence, transcripts, correspondence, and related documents:

- Threatening letter from the Selective Service System

(4 December 1981; certified mail, introduced with return receipt as evidence against me at trial)

- Threatening letter from U.S. Attorney William F. Weld

(19 July 1982; certified mail, introduced with return receipt as evidence against me at trial)

- Information (criminal complaint) and judgment for hugging Russ Ford in an act of solidarity as he was being arrested for refusal to register for the draft

(10 August 1982, Hartford, CT)

- Indictment for knowing and willful failure or refusal to present myself for and submit to registration with the Selective Service System as ordered by the President

(6 October 1982; signed by the foreman [sic] of the Grand Jury and by Asst. U.S. Atty. Robert S. Mueller III)

- Transcript of arraignment, U.S. v. Hasbrouck

(14 October 1982, U.S. District Court, District of Mass., Boston)

- Transcript of trial, U.S. v. Hasbrouck

(15 December 1982, U.S. District Court, District of Mass., Boston)

- Jury verdict, U.S. v. Hasbrouck

(15 December 1982, U.S. District Court, District of Mass., Boston)

- Transcript of sentencing, U.S. v. Hasbrouck

(14 January 1983, U.S. District Court, District of Mass., Boston. The next year, this date would become a holiday in honor of the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.)

[With my mother, Marguerite Helen, in the lobby of the Federal courthouse in Boston after my sentencing for refusal to register for the draft, 14 January 1983. AP photo published on the front page of the Boston Globe and in numerous other newspapers. Most used the caption suggested by the wire service, “Hug from Mom”.]

- Judgment and initial sentence

(14 January 1983)

- Conditions of probation

(14 January 1983)

- Permission to Travel forms

(While on probation, I was required to apply for and receive permission from the U.S. Probation Office each time I wanted to leave the state, even just to visit friends in Connecticut or go for a day hike in southern New Hampshire. My experience being subject to this travel prior permission requirement informs my current work with the Identity Project for freedom of movement as a human right.)

- Letter to U.S. District Judge David S. Nelson

(by Edward Hasbrouck, 5 August 1983)

- Probation violation petition

(18 October 1983)

- Transcript of probation hearing, U.S. v. Hasbrouck

(11 October 1983, U.S. District Court, District of Mass., Boston)

- Transcript of probation violation hearing, U.S. v. Hasbrouck

(22 November 1983, U.S. District Court, District of Mass., Boston)

- Another threatening letter from the Selective Service System

(19 December 1983. Sent to my parents’ address while I was imprisoned; not sent by certified mail. In theory, the government could have tried to prosecute me again if I continued not to register after being released from prison, so I could have taken this letter as a threat of repeated prosecution, But the government made no attempt to prosecute me again, or to follow up in any away on this letter. I assume that this letter was automatically generated and indicates how little weight should be given to most threatening letters from the SSS.)

- Records released by the FBI in response to my Freedom Of Information Act request

(Additional FBI records released separately and still to be scanned)

- Records released by the Bureau of Prisons FBI in response to my Freedom Of Information Act request

(to be scanned)

Additional articles related to my refusal to register for the draft:

- Who Is Edward Hasbrouck?

(Background to my draft registration resistance, other political activism, and personal philosophy; see also Ageism, Youth Liberation, and the the Draft and Why do people oppose the draft?)

- Message to participants in rally outside F.C.I. Danbury

(by Edward Hasbrouck, 14 August 1982)

- Letter to supporters from Mass Open Resistance re: conviction and sentencing of Edward Hasbrouck

(December 1982, after my conviction and before my sentencing)

- Press release from Mass Open Resistance re: probation violation hearing for Edward Hasbrouck

(22 November 1983)

- A letter from Lewisburg Federal Prison Camp

(by Edward Hasbrouck, Resistance News #14, March 1984)

- Advice to nonregistrants singled out for prosecution

(by Edward Hasbrouck, Resistance News #15, July 1984)

- How the Chicago 8 (“Chicago 7”) might have been the Chicago 9

(Eric Weinberger, Dave Dellinger, and my draft resistance; by Edward Hasbrouck, 19 October 2020)

- Voting from prison: A story from 1984

(by Edward Hasbrouck, 3 November 2020; see also To vote, or not to vote?)

- Testimony of Edward Hasbrouck to the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service

(25 April 2019, Washington, DC)

- Articles about the draft from Edward Hasbrouck’s blog

(See also the other articles on this Web site.)

- Let’s run Selective Service up the flagpole and see if anyone salutes

(Letters to the editor of the Boston Globe by Edward Hasbrouck, Stuart Wax, and others, 26 June 2021; PDF)

- Letters in the New York Times about the prosecutions of draft registration resisters:

- Unpublished letter re: draft registration compliance statistics

(Letter to the editor by Edward Hasbrouck, 12 May 1981, in response to article, “Call of the Draft”. This letter wasn’t published, but I did get an unusually defensive personal note from an editor in response.)

- On the Failures of Draft Registration

(letter to the editor by Edward Hasbrouck from Lewisburg [PA] Federal Prison Camp, 21 March 1984: “The issue for Congress and the American people is the failure of draft registration: After almost four years of registration, a million of those eligible haven’t registered…. In such circumstances, it is absurd to think that reinstatement of the draft is a realistic possibility, and it is dangerously naive to make foreign policy commitments that will require a draft.”)

- A Consensus in Support of Draft Registration (1)

(letter to the editor by Wil Ebel, Assistant Director of Selective Service for Public Affairs, 23 March 1984: “Edward Hasbrouck’s letter assailing draft registration is woefully in error. Perhaps we should not expect an incarcerated individual to have accurate and up-to-date information, but your readers should not be deluded by Mr. Hasbrouck’s misrepresentations. Draft registration is not a failure.”)

- A Consensus in Support of Draft Registration (2)

(letter to the editor by Rep. Gerald Solomon: “Edward Hasbrouck called the Solomon Amendment, which denies student aid to those who refuse to register for the draft, ‘a failure.’ The real failure is his inability to separate constitutional rights from taxpayer-financed privileges. We’re hearing a lot these days about ‘yuppies,’ the young urban professionals from the baby boom now on the cusp of political and economic power. I’d hate to think they still cling to the ‘me generation’ notion that the working taxpayers of this country owe them a college education and upward mobility…. If I had my way, those who do not register would lose not only the ‘right’ to a student loan but every other taxpayer-funded benefit.”)

- Courageous Foes of Draft Registration

(letter to the editor by Marjorie Baechler, 7 April 1984: “The remark by Wil Ebel of the Selective Service System that ‘perhaps we should not expect an incarcerated individual to have accurate and up-to-date information’… is an attempt to demean Edward Hasbrouck… and all of us who share conscientious objection to the settling of disputes through the violence of war.”)

- We Still Won’t Go!

(letter to the editor by Edward Hasbrouck, 9 December 1990; PDF of print version as leaflet. “Only 20 nonregistrants were ever prosecuted, the last almost five years ago. The attempt to enforce registration has been abandoned, essentially in failure, while millions continue not to register.”)

- Selected contemporaneous news articles, columns, and letters to the editor about my refusal to register and prosecution:

(additional letters to the editor were published in the Boston Globe, Boston Herald, Wellesley Townsman, Harvard Crimson, and other Boston-area student newspapers; note that many of these news articles have factual errors)

- The signup for draft: two views

(by Herb Gould, Chicago Sun-Times, 20 July 1980)

- Danbury Prisoner Refuses Freedom

(New York Times, 30 August 1982)

- First Mass. draft indictment

(unsigned but written by William Doherty, Boston Globe, 7 October 1982, p. 32)

- Draft Foe Naive, But He Has A Point

(column by Margery Eagan, Boston Herald-American, 14 October 1982, p. 8)

- Protest At Hearing For Draft Resister

(by William Doherty, Boston Globe, 15 October 1982, p. 21, front page of Metro section)

- Who is Ed Hasbrouck, and why is he bucking the system?

(Profile by Melinda Macauley, The Townsman, Wellesley, MA, 9 December 1982, pp. 10-11)

- Draft Count Defendant Is Guilty

(by Berkley Hudson, Providence Journal, 16 December 1982, p. 1)

- Hasbrouck convicted; three supporters arrested

(by Betty Stein, UPI, 15 December 1982. Shortened version published in the New York Times as Massachusetts Man Is Guilty Of Not Registering for Draft.)

- Prosecutor’s the Hero

(Column by David Farrell, Boston Globe, 20 December 1982, p. 1)

- Holiday greetings to U.S. Attorney William Weld

(Unpublished letter to the editor of the Boston Globe by my mother, Marguerite Helen, 22 December 1982)

- Draft Resister Ordered To Do Public Service

(by James Hammond, Boston Globe, 15 January 1983, p. 1)

- No jail for draft resister

(by Betty Stein, UPI, 15 January 1983)

- Judge refuses to jail draft resister

(UPI article with photo published in the Orlando Sentinel, 15 January 1983, p. A-5)

- Hasbrouck sentencing

(Letter to the editor of the Harvard Crimson by public nonregistrant Kenneth Hale-Wehmann, 19 January 1983)

- Court pasted with antidraft stickers

(unsigned but written by William Doherty, Boston Globe, 26 January 1983, p. 21)

- Jury indicts draft protester in court hassle

(by William Doherty, Boston Globe, 10 February 1983, p. 23)

- The new draft resisters

(by David Brisson, East West Journal, April 1983)

- 2 found innocent of assaulting 2 US marshals

(Boston Globe, 20 July 1983, p. 27)

- Treatment of nonregistrant is criminal

(Letter to the editor of the Boston Globe by public nonregistrant John Lindsay-Poland, 2 December 1983, p. 14)

- Profile of Edward Hasbrouck

(feature article by Lisa Mirowitz, December 1983)

[Edward Hasbrouck papers (including archives of the National Resistance Committee and Resistance News), Box 1 of 12, Swarthmore College Library. Photo by Prof. Amy Rutenberg, Iowa State University.]

This page published or republished here 28 April 2023; most recently modified 29 February 2024. This site is maintained by

Edward Hasbrouck. Corrections, contributions (articles, graphics, photos, videos, links, etc.), and feedback are welcomed.