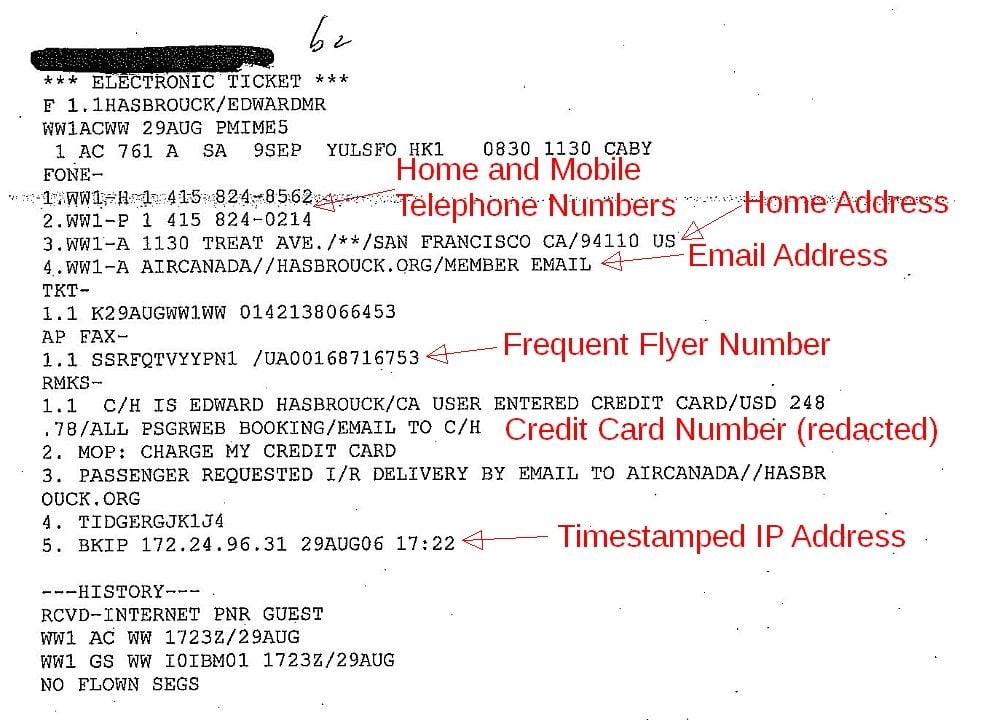

[Excerpt from a simple Passenger Name Record (PNR) from

the file about me kept by the CBP division of the DHS.

Most PNRs have more information than this.]

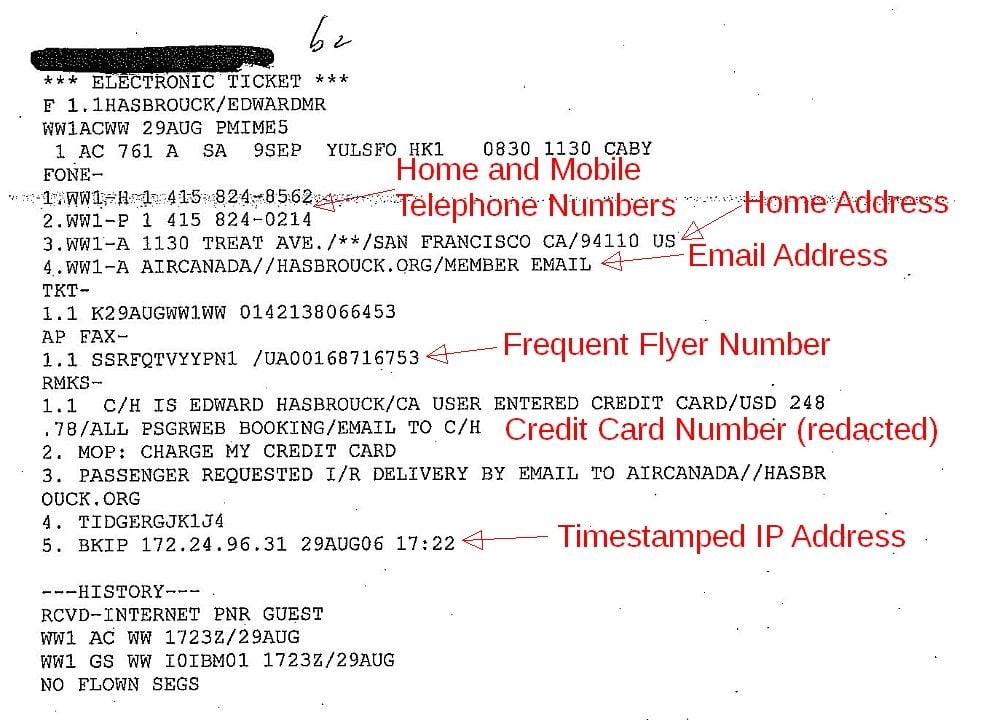

[Excerpt from a simple Passenger Name Record (PNR) from

the file about me kept by the CBP division of the DHS.

Most PNRs have more information than this.]

A Passenger Name Record (PNR) is the basic form of computerized travel record:

[Excerpt from a simple PNR obtained from the CBP division of the DHS. Click image for larger version.

More examples and discussion.]

[Excerpt from a simple PNR obtained from the CBP division of the DHS. Click image for larger version.

More examples and discussion.]

Most travellers have never seen a PNR, and few people know what information is in the PNRs about them, or how it gets there. But with governments using PNR data to decide whether or not to allow you to fly, you need to know what’s in your PNRs. PNRs are the records about each airline passenger that are being used USA government’s passenger surveillance and permission system and “no-fly” lists, and compiled into the Automated Targeting System (ATS) and other databases of the Transportation Security Agency (TSA) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) divisions of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Passenger Name Records are commercial records used to store airline reservations and records related to other travel services. A single PNR can contain data about an entire family or tour group, and about all services for their trip from multiple providers: air and train travel, hotels, car hire, etc.

Perhaps the best way to conceptualize PNR data is as “metadata about the movements of our bodies.” As such, PNR data can be even more intimate than the metadata about the movement of our messages that governments can obtain through Internet or telephone surveillance, or the metadata about the movements of our money obtained from banks and other financial institutions.

PNR data reveals our associations, our activities, and our tastes and preferences. PNRs typically contain credit card numbers, telephone numbers, email addresses, and IP addresses, allowing them to be easily merged with financial and communications metadata.

Police are eager to get more and easier access to PNR data because they know how much sensitive and private information PNRs contain or can reveal.

PNRs are airline records, but few airlines host their own databases. Most airlines store their PNRs in a virtual “partition” in the database of a Computerized Reservation System (CRS). The former U.S. Federal regulations and the regulations which still govern them in Canada and the European Union call these “CRS’s”, but these days they prefer the grander name for themselves of “Global Distribution Systems” (GDS’s). CRS/GDS companies also sometimes distinguish their “CRS” business of hosting PNRs created by travel agencies from their business of hosting (in separate partitions) airlines’ PNRs, but the terms “CRS” and “GDS” are frequently applied to both.

There are only 3 major CRS/GDS companies worldwide (although one was formed by a 2007 merger, and continues to operate two distinct technology platforms under different brand names): Amadeus, Sabre, and Travelport (Worldspan and Galileo).

Of the major airlines in the USA, JetBlue, Alaska, Frontier, and Hawaiian are hosted in Sabre; Delta is hosted in Worldspan by Travelport; Southwest is hosted in Amadeus; and American and United (as discussed further below) are hosted in SHARES.

Google entered the CRS business in 2012 when Cape Air (a small airline based on Cape Cod in Massachusetts) migrated to a new system provided by Google’s ITA Software division.

Some airlines have built or licensed all or part of their own hosting systems, with limited connections to the CRS’s so that travel agencies can make reservations through their CRS’s. Navitaire, a wholly-owned U.S. subsidiary of consulting and outsourcing conglomerate Accenture, provides its “New Skies” and “Open Skies” hosting services (and in some cases, depending on the airlines, connectivity to the major CRS’s and through them to travel agencies) for many airlines, primarily “low-cost” and “ticketless” airlines, including both airlines based in the USA and airlines based abroad such as Ryanair (Ireland) and Wizz Air (Poland).

United Airlines (since its merger with Continental) and some other airlines in the USA and abroad (notably including Virgin Atlantic) use the SHARES system. Shares was built and run by EDS, which was acquired by Hewlett-Packard in 2008. SHARES doesn’t have travel agency subscribers, only airline users, and isn’t considered a CRS or regulated as one. But in many other respects SHARES resembles a CRS, and it has interfaces to all four major CRS’s. In 2009, HP was reported to be developing a new system derived from SHARES to be called “Jetstream” and eventually to be used by American Airlines. After American Airlines files for bankruptcy protection from its creditors in 2012, there were conflicting reports about whether or how the Jetstream project and the relationship between American and HP would be continued.

United Airlines was one of the original users of Galileo (Apollo). At one time United announced it would be migrating to Amadeus for compatibility with Lufthansa and other Star Alliance members hosted in Amadeus, but in 2009 TheBeat.travel reported that the migration plan had been indefinitely suspended. Later, as part of its merger with Continental (which was already using SHARES), United migrated from Apollo to SHARES in March 2012.

All of the big four CRS’s, and EDS/HP’s SHARES hosting system, were built on IBM’s Transaction Processing Facility (TFP) platform. Ongoing efforts to migrate them off TFP and mainframe platforms have proven extremely difficult, slow, and expensive.

Amadeus is the only one of the four major CRS’s based in the European Union rather than the USA. But Amadeus customers are not limited to European or other non-US based airlines or travel agencies. All Southwest Airlines reservations are hosted in Amadeus, for example. And even airlines that outsource the storage of their own master PNRs to Amadeus typically have agents who use Sabre, Galileo, and Worldspan. All of the major USA-based CRSs have substantial travel agency and airline market share in the EU, as does Amadeus in the USA.

CRS’s/GDS’s have the same relationship to travel data that credit bureaus have to financial data: they centralize and store vast amounts of information about you, but they get the information through intermediaries, they remain in the background, and they have minimal direct contact with the people on whom they keep files.

(Money and financial data for airline tickets sold by travel agents in the USA are sent to airlines through another intermediary, the Airlines Reporting Corporation (ARC), and through the Bank Settlement Plan in other countries. Although ARC receives data collected by travel agents in their capacity as agents of airlines based in Canada and the European Union, among other places, and thus subject to the data protection and privacy laws of those jurisdictions, ARC has no publicly-disclosed consumer privacy policy — their privacy policy covers only visitors to their Web site — and makes no apparent effort to comply with the privacy laws of any jurisdiction outside the USA. It’s unclear to what extent ARC receives or retains full PNRs.)

CRS’s/GDS’s don’t just store data: they also are the center of travel networking. CRS’s/GDS’s connect airlines to each other, to travel agencies, and to car rental companies, hotels, cruise lines, tour operators, and other providers of travel services. PNRs obtained from or via CRS’s are also used by an entire industry of secondary and tertiary recipients, aggregators, and users of this data, including data mining and marketing companies.

The PNR data ecosystem was designed to maximize seamless, frictionless, real-time global availability of this information. The network of CRSs was the first and remains one of the largest global, real-time, outsourced, “cloud” data storage and retrieval systems, connecting tens of thousands of travel companies and storing business records about hundreds of millions of individuals.

There are insufficiently granular controls on PNR access, with no geographic or purpose limitations on access to any PNR by any CRS user, anywhere in the world. Each node in the global network is a point of vulnerability to governments or criminals, for purposes that can include surveillance, industrial espionage, stalking, domestic violence, or kidnapping:

CRSs can be, and have been, hacked. It’s actually quite easy to hack a CRS and obtain PNR data without being detected. I’d be happy to discuss some of the vulnerabilities I know about with any CRS operator, airline, legislator, or data protection official who is willing to listen.

There are no records of which CRS user has retrieved a PNR, where in the world, or for what purpose. So it’s impossible to know how often PNR data is stolen or leaked, who the most common attackers are, where they are located, or how they use PNR data they have obtained surreptitiously or improperly. Airlines do not know who has retrieved PNR data about their passengers, or where in the world CRSs have transmitted this data in response to queries by CRS users.

In response to my complaints to European data protection authorities, major European airlines have admitted that even the EU-based Amadeus CRS has no access logs. Without access logs or geographic or purpose limitations on access, even an airline that relies solely on Amadeus, and doesn’t allow its agents to use any of the US-based CRSs, is unable to provide a complete accounting of disclosures or cross-border transfers of PNR data, as required by EU data protection law.

These deep-rooted and systemic security problems in the commercial PNR data infrastructure predate governments’ efforts to obtain root access to CRSs or to construct government mirror copies of CRS databases of PNRs. Unless the CRSs are first secured, it will be impossible to control or contain how governments use their mirror copies of PNRs.

Whenever you make a reservation, a PNR is created. PNRs cannot be deleted: once created, they are archived and retained in the CRS/GDS, and can still be viewed, even if you never bought a ticket and cancelled your reservations.

We don’t know in what form the DHS stores PNR data. In 2010, after years of DHS stonewalling on my requests, I sued CBP under the Privacy Act and FOIA to find out what PNR and other travel data they have about me, how it is indexed, and who else they have “shared” it with. There’s been no trial or ruling yet on that lawsuit.

Both CRS/GDS master copies of PNRs, and the mirror copies of PNRs and PNR-derived travel data kept by the DHS, are vulnerable to abuse by stalkers (as in this case) or identity thieves.

All airlines and CRS’s/GDS’s include an audit-trail or change log feature called the “history”. Once a PNR is created, each entry is logged in the PNR “history” with the date, time, place, user ID, and other information of the travel agent, airline staff person, or automated system who made the entry, as well as the name of the traveller or other person, such as a business associate or family member, who requested the entry or change. Each entry in each PNR, even for a solo traveller, thus contains personally identifiable information on at least 2, often 3 or 4, people: the traveller, the travel arranger or requester, the travel agent or airline staff person, and the person paying for the ticket.

In addition to travellers, PNRs contain data on individuals who made reservations, but did not actually travel — even if they never even purchased tickets. To “cancel” or “delete” a segment or data element in a PNR means to move that item from the “active” or “live” portion of the PNR to the permanent “history” portion. To “cancel” an entire PNR means to move it from live or active storage to archival storage.

CRS’s retain flown, archived, purged, and deleted PNRs indefienitely. It doesn’t really matter whether governments store copies of entire PNRs or only portions of them, whether they filter out certain especially “sensitive” data from their copies of PNRs, or for how long they retain them. As long as a government agency has the record locator or the airline name, flight number, and date, they can retrieve the complete PNR from the CRS. That’s especially true for the U.S. government, since even PNRs created by airlines, travel agencies, tour operators, or airline offices in other countries, for flights within and between other countries that don’t touch the USA, are routinely stored in CRS’s based in the USA. ((While this is routine, I’ve never heard of a travel agency or tour operator in Canada, the EU, or anywhere else that tells its customers that it has outsourced its customer database of PNRs to the USA, or asks potential customers for permission to create and store their PNRs and profiles in a system hosted in the USA.) Even Amadeus, the one major CRS based outside the USA, has offices in the USA with access to the full Amadeus PNR database.

To the best of my knowledge, no CRS/GDS or airline hosting system includes a mechanism for truly deleting or purging PNRs pertaining to cancelled or unticketed reservations. A PNR can be cancelled, but the audit trail or “history” of the PNR, showing when and by whom each entry in the PNR was made, is always retained at least until the last date of an of the reservations, active or cancelled, in the PNR. After that, it’s moved to permanent archival storage.

Each PNR contains a change log (“history”), but I’ve never seen or heard of a CRS or PNR handling system that includes an access log in the PNR. So unless logs are kept at the system level (as is sometimes done, for at least a short time, by a CRS for debugging or other purposes), it is impossible to know who has actually retrieved or viewed any particular PNR, or any of the data in it, or from which country or countries that data has been retrieved. None of the European airlines from which I have requested my PNR data has provided me with any access logs, even though they are required by EU data protection law to disclose transfers of personal data to entities outside the EU.

PNRs also contain data on individuals who never travel by air at all: the vast majority of car rental and hotel reservations, and some bookings for cruises and other travel services, made through travel agencies, are made through a CRS/GDS and entered into a PNR, even if they do not involve air travel. Because of the use of PNRs in a CRS/GDS as a CRM system and the basis of most travel agency accounting systems, most corporate and many leisure travel agencies create PNRs for all reservations of any type, whether or not they were actually booked through a CRS/GDS.

Each entry in a PNR “history” includes a “received from” field identifying the person who requested the reservation or change. PNRs thus include personally identifiable information on travel arrangers, such as corporate and professional personal assistants and administrative staff, travel managers, event organizers, and family members and friends assisting with travel arrangements.

PNRs also include extremely detailed, personally identifiable data on travel industry personnel, particularly travel agents and airline reservation, check-in, and ticketing staff. Each entry in a PNR history includes a field identifying the unique “agent sine” or log-in ID of the person making the entry, along with the city or “pseudo-city” (airline office or travel agency branch or location) and the LNIATA or “set address” of the terminal or data connection on which the entry was made (the CRS/GDS or airline hosting system counterpart of an Internet IP address) and the exact time of the entry. In the aggregate, PNRs thus provide a comprehensive and extremely detailed record of every entry made by tens of thousands of travel agents and airline reservation staff: what was entered, when, where, by whom, and for whom.

When a travel agent makes a reservation, they enter data on a CRS/GDS terminal, and create a PNR in that CRS/GDS. If the airline is hosted in a different CRS/GDS, information about the flight(s) on that airline is sent to the airline’s host system, and a PNR is created in the airline’s partition in that system as well. What information is sent between airlines, and how, is specified in the Airline Interline Message Procedures (AIRIMP) manual, although many airlines and CRS’s/GDS’s have their own direct connections and exceptions to the AIRIMP standards.

If, for example, you make a reservation on United Airlines (which outsources the hosting of its reservations database to the Galileo CRS/GDS) through the Internet travel agency Travelocity.com (which is a division of Sabre, and uses the Sabre CRS/GDS), Travelocity.com creates a PNR in Sabre. Sabre sends a message derived from portions of the Sabre PNR data to Galileo, using the AIRIMP (or another bilaterally-agreed format). Galileo in turn uses the data in the AIRIMP message to create a PNR in United’s Galileo “partition”.

If a set of reservations includes flights on multiple airlines, each airline is sent the information pertaining to its flights. If information is added later by one of those airlines, it may or may not be transmitted back to the CRS/GDS in which the original reservation was made, and almost never will be sent to other airlines participating in the itinerary that are hosted in different CRS’s/GDS’s. So there can be many different PNRs, in different CRS’s/GDS’s, for the same set of reservations, none of them containing all the data included in all of the others.

If you are a regular customer or have a corporate or frequent flyer account with an airline or travel agency, your account information is typically stored in a “profile” in the CRS/GDS that is automatically associated with, and often copied into, each PNR created for you. That profile might include all the credit cards you regularly use (even if you aren’t using them for this purchase); alternate addresses, phone numbers, and emergency contacts; names and other information on your family members or business associates who sometimes travel with you (even if they aren’t on this trip); notes about your tastes and preferences (“prefers king bed”, “prefers room on low floor in hotels”, “always request halal meal”, “won’t fly on the Jewish sabbath”, “uses wheelchair, can control bowels and bladder”; “prefers not to fly Delta Airlines”); personal notes intended for the internal use of the travel agency (“difficult customer — always changing his mind”); department and project billing and approval codes for corporate travel; all your frequent flyer numbers (even ones you aren’t using on this trip) and a wide variety of other information.

If you make your hotel, car rental, cruise, tour, sightseeing, event, theme park, or theater ticket bookings through the same travel agency, Web site, or airline, they are added to the same PNR. So a PNR isn’t necessarily, or usually, created all at once: information from many different sources is gradually added to it through different channels over time.

When a ticket is issued, that is recorded in the PNR; if it’s an e-ticket, the actual “ticket”, as defined by the airline, is the electronic ticket record in the PNR. When you check-in, the claim check numbers and the weights of your bags are added to the PNR. If you don’t show up for a flight on which you are booked, that fact is logged in the PNR.

Whenever anything in the reservation is added, changed, or cancelled, that can be communicated to the CRS/GDS that holds the original PNR. (It isn’t always, but it always can be.) If you call the airline or visit its Web site, and request seat assignments, that is entered in the PNR. If your travel agency or the airline uses Sabre, and you look up your airline reservation on Sabre’s “VirtuallyThere.com” Web site, and add a car reservation through VirtuallyThere.com, that goes in the same Sabre PNR.

(Each of the 4 major CRS’s/GDS’s has a Web site that gives anyone access to PNR data — in three of the 4 cases with no password at all, just the reservation number printed on every ticket.)

Most travel agencies use the CRS/GDS as their primary customer database and accounting system. So they store all customer data in CRS/GDS profiles, and create “manual” PNRs for every reservation, even if the reservation wasn’t made through the CRS/GDS, and even if the data in the profile isn’t actually required for reservations.

Each PNR contains a section for free-text “remarks” entered by airline, travel agency, tour operator, and third-party call center and ground handling contractor staff. Most travel industry personnel don’t realize that anything they enter in a PNR — for example, a free-text remark to warn their colleagues about a difficult or verbally abusive or insulting customer — will be transferred to governments around the world, included in permanent government files about the person, and used as part of the basis for profiling the person and deciding how the government will treat them or whether they will be allowed to fly. Government mirror copies of PNRs include internal travel industry staff chatter and gossip never intended to be shared with the police.

Between them the 4 main CRS’s/GDS’s have a record of everyone who has even considered travelling, and made a reservation, whether they bought a ticket or took the trip or not. They also have a record of every entry made by a travel agent or airline reservation staff person.

PNRs show where you went, when, with whom, for how long, and at whose expense. Behind the closed doors of your hotel room, with a particular other person, they show whether you asked for one bed or two. Through departmental and project billing codes, business travel PNRs reveal confidential internal corporate and other organization structures and lines of authority and show which people were involved in work together, even if they travelled separately. Particularly in the aggregate, they reveal trade secrets, insider financial information, and information protected by attorney-client, journalistic, and other privileges.

When I reviewed PNR data provided by the DHS to Julia Angwin, a former Wall Street Journal reporter, I found — not surprisingly — that the newspapers’s corporate travel agency had routinely included notes in PNRs describing the journalistic purpose of reporters’ trips. Along with everything else in the PNRs, this became part of journalists’ permanent files with the DHS. The newspaper’s lawyers were unaware that communications between reporters and their’ editors about their journalisitc work were routinely becoming part of government files. (Julia Angwin, Dragnet Nation, Times Books, 2014, pp. 92-95)

Through meeting codes used for convention and other discounts, PNRs reveal affiliations — even with organizations whose membership lists are closely-held secrets not required to be divulged to the government. Through special service codes, they reveal details of travellers’ physical and medical conditions. Through special meal requests, they contain indications of travellers’ religious practices — a category of information specially protected by many countries.

PNRs for reservations made or changed online routinely include IP addresses and timestamps to enable them to be cross-referenced with Web server logs.

In the USA, the Transportation Security Administration said its CAPPS-II airline passenger profiling system (later modified and renamed Secure Flight) “would provide TSA only with the information all airlines will collect during the normal reservation and ticketing process.” TSA spokesperson Brian Turmail told me that would initially consist of each passenger’s name, date of birth, address, and phone number. “Airlines already require three of these four items,” he claimed. But that’s just not true: airlines don’t, in general, require any of these items in their PNRs.

Airlines don’t collect most passenger information — travel agents do. Most passengers never deal with the airline until they check in for their flight at the airport. And standard travel agency procedures make them function, in practice, as quite effective “anonymizing proxies” for travellers.

If a travel agent enters an address in a reservation at all, which they don’t have to do, the default is to enter the agency’s address, not the passenger’s address. The passenger’s address is an additional, optional item, and not necessarily sent to the airline even when it’s entered in the agent’s records. Likewise the passenger’s phone number: the default entry in a reservation made by a travel agency is the agency’s phone number, with the passenger’s phone number an additional, optional item. Only one address and phone number is generally entered for each reservation, even if the travellers have different addresses and phone numbers.

Even before publishing its CAPPS-II and later “Secure Flight” proposals, the USA Department of Homeland Security, which includes the TSA, had made a separate request for access to PNR and “passenger manifest” or Advance Passenger Information (API) data on all international flights to the USA.

In response to questions from European Union authorities as to what data might be included in PNRs, the DHS provided a list in May 2003 of 39 types of data that might be included in PNRs, in addition to the four additional items (name, home address, home phone number, and date of birth) proposed to be required for CAPPS-II. The DHS didn’t say that all 39 of these data elements are, or would have to be, in every PNR. The DHS wants the entire PNR, whatever it includes. The point of the list was to disclose all the types of information that might be transferred to the DHS if the DHS gets the entire PNR, in order to satisfy the requirement of EU law that such data transfer be disclosed.

In reality, few PNRs contain all of the listed items, and many PNRs contain other items. So the list of items serves more to show the DHS’s ignorance of what data is contained in real PNRs, rather than as a comprehensive list of possible PNR contents or as any list of “required” data.

(The list of possible PNR data elements was first released in response to requests from European passengers for information on how their travel records had been used, and what information had been transferred to the USA. In the USA, there is no comparable privacy law requiring disclosure to passengers of how their travel records are used.)

The final list of 34 data elements described in the May 2004 Undertakings (nonbinding unilateral statements) of the DHS to the European Union, includes “Advance Passenger Information” (API) as one of the categories of data in PNRs. This is only sometimes true: many airlines enter and store API data separately from PNRs. API data is collected, stored, and forwarded to governments (typically to the immigration authorities of the destination countries of international flights, after the flight has departed but before it arrives), originally as a way to expedite customs and immigration processing by allowing destination authorities to start reviewing the passenger manifest while the flight is still in the air.

At first, demands for API data were limited to the data that authorities at the destination would eventually be able to obtain by inspection of passports or similar travel documents. But first the USA, and more recently some other governments, have begun demanding that airlines collect additional information, such as passenger addresses, phone numbers, etc.

Although the DHS has continued to claim in its “Undertakings” to the European Union that, “Most data elements contained in PNR data can be obtained by CBP [the DHS Bureau of Customs and Border Protection] upon examining a data subject’s airline ticket and other travel documents”, that isn’t true, even for international flights. As I’ve explained in my blog in detail as part of my analysis of the “undertakings”, 17 of the 34 listed data elements could never be discerned from tickets or other travel documents, and in most cases only 8 of the 34 fields could be determined from inspection of tickets.

API data can be entered either in PNRs themselves, or in separate databases. In most cases the airline has no direct contact with the passenger until they check in for their flight, and PNR data is hosted in systems, and reaches the airlines from travel agencies and other intermediaries through interfaces, many of which still have no standard fields or formats for API data. So most airlines have collected and entered API data only at check-in, and entered it in databases separate from those used for PNRs. Until standards are agreed, airlines have found the labor cost of having their check-in staff collect and enter API data to be less than what it would cost to modify reservation systems and interfaces to support collection, entry, and transmission of API data in PNRs by travel agencies, according to each country’s different API demands.

The collection, storage, and forwarding of API data (unlike PNR data) serves no business purpose for airlines. It is solely a passenger surveillance and immigration law enforcement function carried out by the airlines on behalf of governments. Airlines have, quite properly, resisted the imposition of this unfunded mandate to carry out passenger surveillance and monitoring on governments’ behalf. In a 2004 “Statement of Principles” on API requirements submitted to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), which was considering standards for API data, the International Air Transportation Association (IATA), the global airline cartel, took the position that, “Required API data should be limited to the data contained in the machine-readable zone of travel documents or obtainable from existing government databases, such as those containing visa issuance information.”

Current USA requirements for API data already exceed that recommendation; Secure Flight goes even further. In comments filed with the USA government in 2003, IATA said that the cost of providing API data to the USA government would be “substantially higher” than IATA’s initial “extremely conservative” estimate of US$154 million. Providing or requiring additional data in PNRs, or collecting and entering API data in PNRs when reservations are first made, would be much more expensive than that. My own extrapolation when these proposals were first made was that collecting, entering, and delivering the additional PNR data required by the US government for CAPPS-II would cost airlines, travel agencies, and CRS’s US$1 billion or more.

IATA’s briefing paper to ICAO on government mandates for PNR data notes that, “Any movement to impose changes on the industry with respect to the way that PNRs are constructed, stored or exchanged would require a massive restructure of the entire industry’s underlying IT base. While no firm analysis has been undertaken to identify the final cost of such a restructuring across the industry - including within the Travel Agency community - some in the industry have estimated that the costs could conceivably exceed US $2 billion.”

By the time the APIS and Secure Flight rules were in effect, the DHS had admitted this by increasing its official estimates of the costs imposed on travel companies to build these surveillance and control mechanisms into their business and IT infrastructure to more than US$2 billion. Travel compnaies continued to protest that this was a severe underestimate of their expenses, probably becuase the DHS still didn’t understand the complexity of the PNR data ecosystem anf the number of intermediate layers and components that would need to be modified, from the AIRIMP protocol layer up, to support full throughput of new data elements.

API “guidelines” have been adopted by the World Customs Organization (WCO), IATA, and ICAO, and have been used as the basis for API formats in the AIRIMP protocol for messages between airlines and CRS’s (see the links below to these and related technical references). But these API guidelines still have not been agreed to by all governments that have, or are considering, API requirements. (“Customs” relates to the movement of goods, and API to the movement of passengers. So it’s unclear to me why the WCO was involved in developing the API guidelines, much less the nominal lead organization for them.)

The bottom line is that PNRs contain a great deal of confidential and sensitive information deserving of strong privacy protection, but not necessarily even the most basic information needed for positive identification or “profiling” of travellers. And the Secure Flight and APIS systems rely primarily on additional data that didn’t used to be included in PNRs at all, but that travellers are being required to provide and travel agents and airlines have been required to modify their computer systems and reservation procedures to collect and transmit to the government, at a financiaol cost of billions of US dollars (in addition to its cost in loss of freedom and civil liberties) that is ultimately have to be borne by travellers (in higher fares and “security” fees) and taxpayers.

[Disclosure:I have been a paid affiliate of Airtreks.com, which subscribed to the Amadeus, Sabre, and Galileo CRS’s.]

About | Bicycle Travel | Blog | Books | Contact | Disclosures | Events | FAQs & Explainers | Home | Mastodon | Newsletter | Privacy | Resisters.Info | Sitemap & Search | The Amazing Race | The Identity Project | Travel Privacy & Human Rights

This page published or republished here 5 October 2020; most recently modified 8 January 2024. Copyright © 1991-2024 Edward Hasbrouck, except as noted. ORCID 0000-0001-9698-7556. Mirroring, syndication, and/or archiving of this Web site for purposes of redistribution, or use of information from this site to send unsolicited bulk e-mail or any SMS messages, is prohibited.